38 years ago one of Birmingham’s most vibrant multi-cultural suburbs hit the headlines after rioters went on the rampage. Documenting the events that happened in September 1985 was Filmmaker and Photographer Pogus Caesar. Having just got home from work that day he received a call that would lead to lasting images imprinted on his mind for the rest of his life. Pogus unravels the details of the day.

“I got home from work that day and someone said to me: ‘you’ve got to get back to Handsworth, it’s on fire’. So I turned on the radio and television and they were talking about this incident in Handsworth where a guy had been stopped for a minor traffic offence. I don’t think he had a tax disc and the police had stopped him. He had then run to the Acapulco café and it started from there. At about 7 o’clock the rioters set the Villa Cross alight. The police tried to stop it but the rioters said let it burn.

“What I did was grab my camera and film get in to my car and go up to Newtown. I went on to Lozell’s Road – they call it the Handsworth riots but it actually happened in Lozells – and then just saw this amazing scene of running battles, police being pelted with stones, cars overturned, people being attacked and shops being looted. There were White, Asian, Afro-Caribbean – essentially young people – who were causing the fracas.

“It was between the people and the police. Some people say it was a race riot but it was essentially between people and the police. One can say it stemmed from when that guy got stopped but over the past years there had been a lot of issues around racism, people getting stopped and searched and police harassment. There were issues around bad housing, education and job opportunities so in a way the explosion happened that day but the fuse had been lit a long time ago. Tensions were running high.

“I’m not the voice of the black community, I am just one person that was there but over the years you could see the resentment that was building up. You could say that if that guy hadn’t been stopped over the traffic offence then we probably wouldn’t be having this conversation right here.

“Just days before the Handsworth carnival had been a great success. Thousands of people revelling in the streets and then the next days it went from light to darkness. As a photographer it was my job to document what I saw. There was a whole range of images that are there and I would like to think that 20 years on they are a social document. Birmingham needs to know what happened. There are a lot of people that would never know the riots went on.

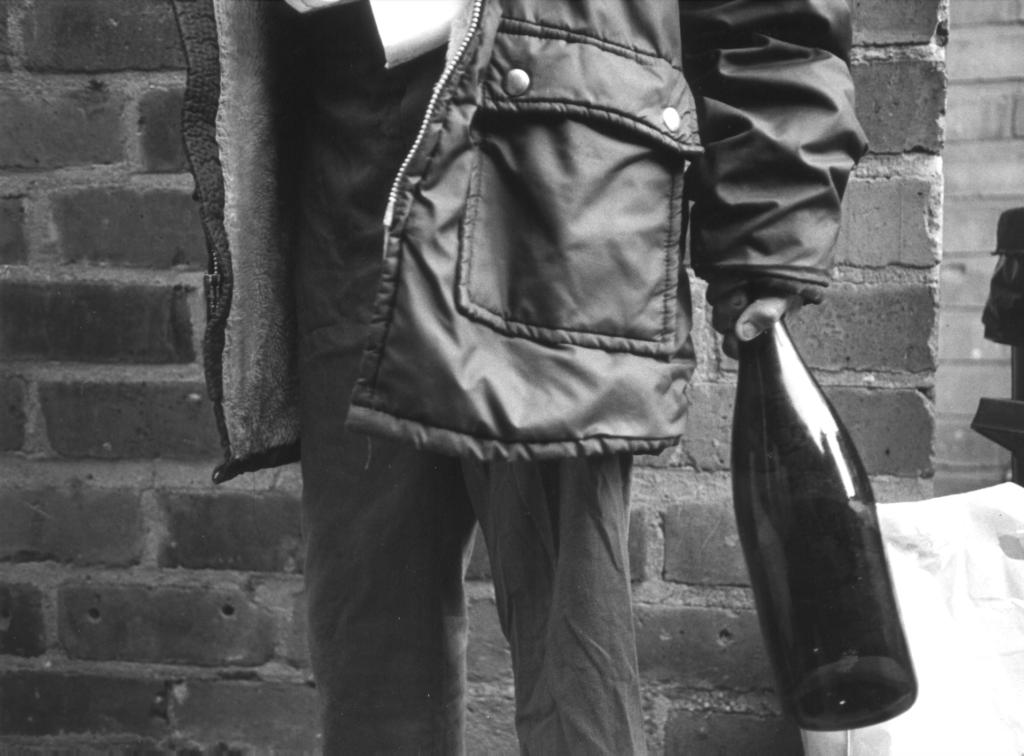

“A lot of people don’t have a problem having their picture taken as long as you don’t show their face but there are a number of images that involve people in elements of criminality, like the boy with the bottle or rioters with balaclavas. I knew a lot of people in Handsworth so I could move among them. I use a camera that requires you to get in close to the subject. Some people say ‘don’t take my photograph’ and I wouldn’t. There were an awful lot of images, when I look back now, I am thankful that I didn’t take them because I wouldn’t want them in my collection. The temptation would be to publish them and I had seen an awful lot of bad things happen and I don’t want to be reminded of them.

“The community was angry that this could happen because we had the riots of 1981 – the National Front were really involved in causing that. This time around because it was such a minor incident of a guy getting stopped that it could escalate and really tear down the whole community. Handsworth is a very vibrant place: it is one of the most multi cultural places in the whole of Birmingham. If you look back now years on it has changed for the better in some ways but the money that was promised to be put in to the community, a lot people can’t see it. There are still a lot of empty shells and gaps between building which have never been replaced so it does demoralise the community so once again it is our community that is being destroyed and once again it is our community that is in the newspapers.”