THE SUN NEVER SETS: MATTHEW KRISHANU

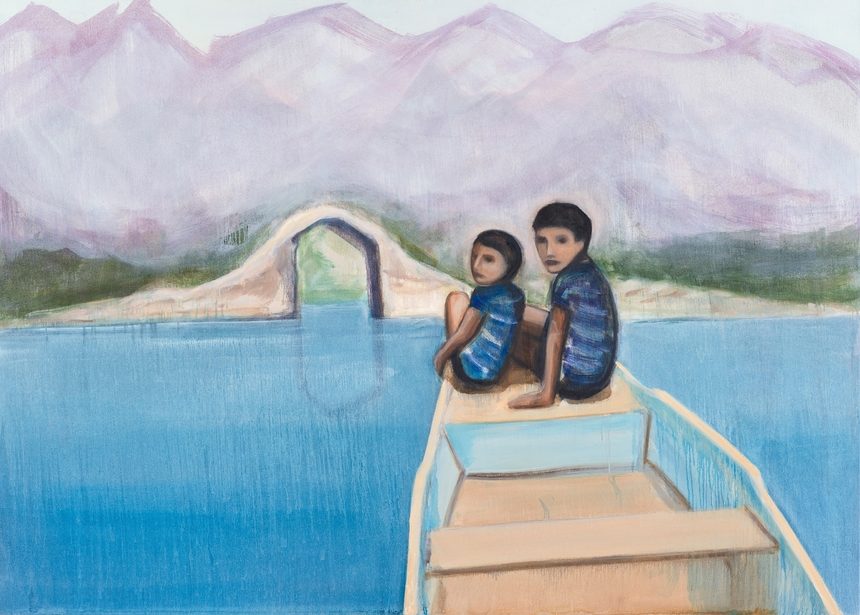

Born in Bradford and now London based, Matthew Krishanu spent eleven years in Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka. The artist was inspired by his years spent in Dhaka and the bond he shares with his brother. His work also takes on an exploration of the childhood gaze of young boys in an atmospheric and complex world of expatriates, missionaries and expansive landscapes.

Matthew, where does your story begin?

It began in Bradford, where I was born. My father was working as a curate there, having trained at theological college nearby. Shortly after my birth my parents moved to Selly Oak, in Birmingham, to undertake missionary training, in preparation for a move to Bangladesh – a country neither of my parents had been to previously. While in Bangladesh my father worked as a priest, and my mother founded and directed a women’s theological organisation – reinterpreting scriptures from women’s perspectives – which went on to inform her PhD in Bristol some ten years later.

What was school like in Bangladesh?

My brother and I started at an ex-pat school, with a Christian Evangelical underpinning. It was problematic in that all of my teachers were White – and most of the students were White and it was an ex-pat enclave, in which my brother and I as mixed-heritage children were something of outsiders. Then we moved to a local school where nearly all the students were Bangladeshi Muslims, and they were generally extremely wealthy – an elite class that went on to Oxford, Harvard and Yale, so a lot of my school friends are dotted around the world now.

And your father was leading church services?

Yes, my father was taking services in English for the ex-pat community, at 10am, but before that (at 8am or so) there was a huge Bangladeshi congregation, and he was the only White man in the room (a theme that is central to my Mission paintings). They were separate services: one in English and one in Bengali. And credit to him – I’ve never mastered Bengali like my dad did. For a White man going to Bangladesh in his thirties, it’s impressive he was soon reading the Old Testament and leading services in Bengali. He learned Bengali from my mother.

Was your family’s social time divided between the ex-pats and the local community?

Absolutely – I would notice the change of language, body language, and atmosphere when visiting really poor Christian worshippers. It was completely different when we were with the ex-pats, who had beer and chauffeur-driven cars. There was a place called Gulshan, the ex-pat enclave in Bangladesh, where all the houses were very fine looking and have air conditioning and so on. This was not my family’s lifestyle – we had a fairly simple existence (relative to the wealthiest ex-pats) but we had all these different worlds of socio-economic and cultural backgrounds to interact with.

Were you living in a big city?

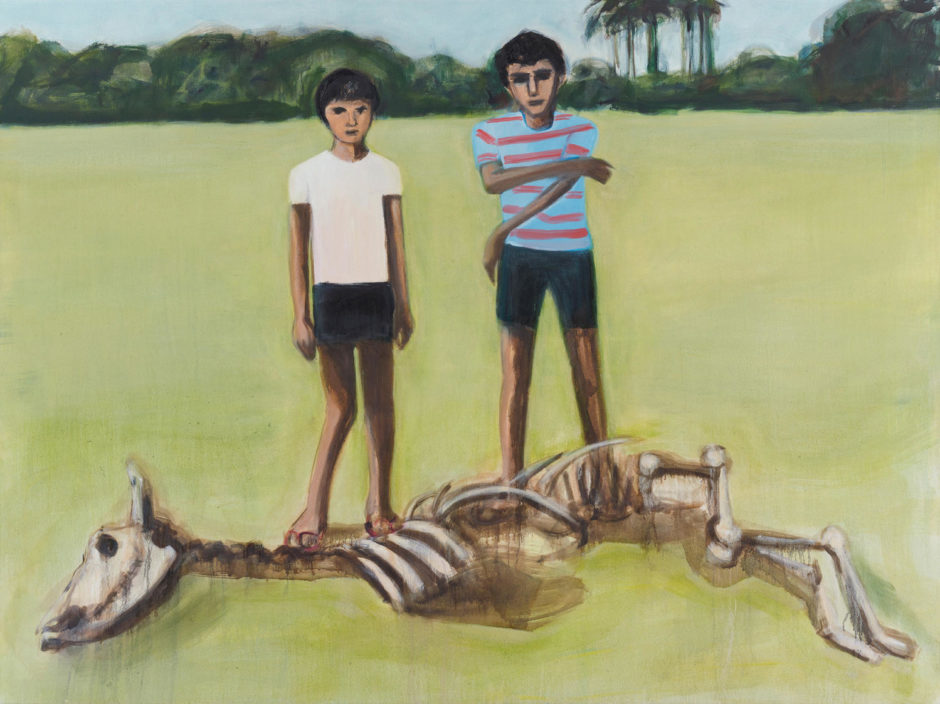

Yes, we were in the capital, Dhaka, and even then it was overpopulated, overbuilt and polluted. We regularly went to outlying cities like Chittagong, Sylhet, and Mymensingh, which is where my painting Skeleton (2014) is set. My father would also provide ministry for rural communities outside Dhaka. One of my ‘Mission’ series of paintings is of him outdoors with big trees and people sitting out on the ground. During times such as the cyclones and flooding, with the amount of death and destruction that they wreaked, he would go and lead services for Christians in rural contexts, but essentially it was a busy urban church. There was one period which is very vivid in my memories, probably between the ages of six and eight, when we were living in a flat underneath the church itself, and that was the basis of several of the ‘Mission’ paintings – the ones with bunting and streamers. The church was a place where my brother and I would go and play on days when services weren’t being held. We would play with the communion bread and the wine, and the cross with its backlights. The whole artifice of it was kind of a playground for us.

Many of your paintings, especially from the ongoing ‘Another Country’ series, are of you and your older brother playing.

Yes, in the paintings he’s the taller one, I’m the smaller, slightly awkward one. He’s dominant in the painting – that’s deliberate. In Skeleton, he’s the one standing on the right with his arms crossed. The only exception to that older brother/younger brother power relationship, I think, is in Limbs (2014) where I’m wearing red, and he’s wearing blue and is a little behind me, so the power swaps a bit. He was a classic big brother (if anyone was going to pick on me it had to be him, not anyone else). I think he was a shield for me, culturally speaking, through all of it.

What proportion of the works in ‘Another Country’ are from when you were living there, as opposed to holidays from later on?

They were all from when we were living there. In 1992 we left Bangladesh and moved to Southampton – I would have been twelve years old. So I started secondary school and became a teenager just a few months after. The rift between pre-adolescence and adolescence was encapsulated in that period – after that I felt like the past was a foreign country, that I’m still living there in part of my mind. As a child, experiencing things like the monsoon or coming across cattle bones (I can feel it in my chest just talking about it) was immediate and rooted. And then when I went back to England I just remember the awkwardness – even in the photos I look awkward, with the style of my clothing, and I grew my hair – I was quite an uncomfortable teen. It was a literal cut off point, after which the photos don’t visually appeal to me as source material (there was something of the light that the old photos caught which I like). So no material taken after moving away from Bangladesh has yet fed into ‘Another Country’ – although I do plan to visit again soon, so that may well change.