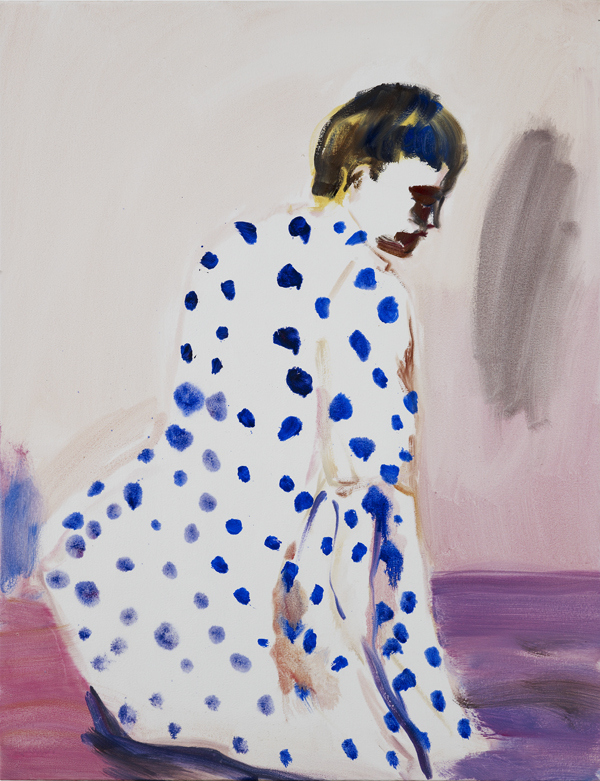

The cast of characters that populate the paintings of Manchester-based, Chelsea MA graduate Lindsey Bull are a curious bunch. We might find a quirky middle-aged couple dressed for a party, the woman wearing a gregarious headpiece but both with emotionless expressions (Couple, 2015), younger characters looking like they are from some terribly dour 80s-inspired synth pop band (Blue Suit, 2015), or a boyish young lady (or girlish young man) sat wearing a dotty blue dress, his/her back towards us (Kneeling, 2016).

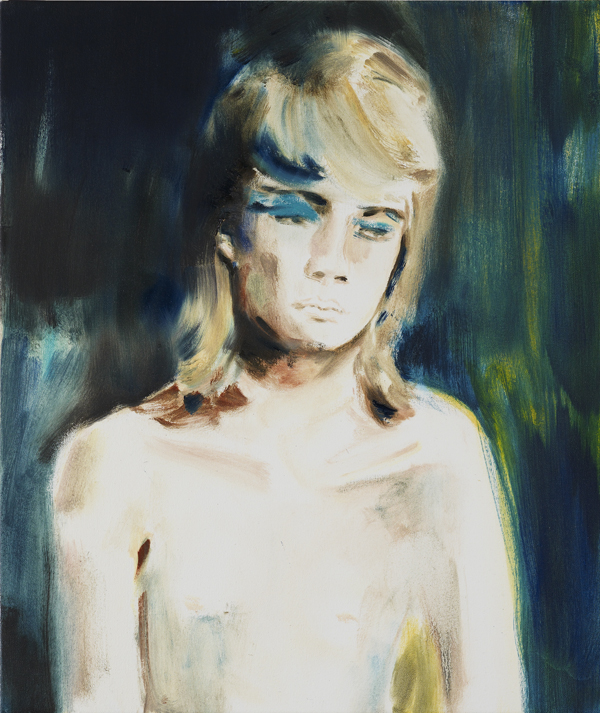

Some of these characters seem shy and retiring, as if caught surreptitiously by a camera, or held against their will by the eyes of the viewer. Often tinged with melancholy, and without so much as a smile in sight, we find people of all sorts looking thoughtful, introspective, self-conscious, serious, depressed. A headshot of a young person with longish straggly hair and dark eyeliner, wearing a blue blazer, white shirt and dark bow tie might be a goth forced to attend a wedding, or perhaps a concert pianist with radical subcultural affiliations. Again, it’s hard to tell whether we’re looking at a boy or a girl, and it is perhaps this underlying androgyny that is the image’s punctum, or visual power.

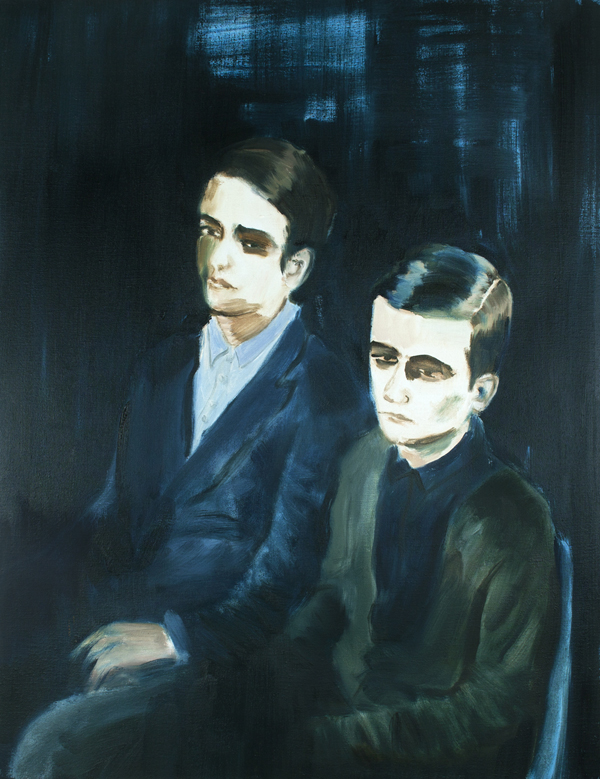

In another work, Statues (2015), two young men are depicted sat in a dark space, wearing equally dark jackets and trousers, their white faces starkly illuminated against the darkness. They look wan, tired, bored, sad, and possibly deprived of their five a day. Who knows where they might be and why they might be there – the narrative possibilities are as limitless as our imaginations; they could be in the audience at a particularly dull episode of Mastermind, or smartly dressed criminals being detained after a failed late-night drugs run. Are they brothers, friends, lovers, colleagues, acquaintances or complete strangers? It is clear that Bull relishes offering us as few clues as possible to be able to answer such questions, but provides us with just enough that we can’t help but want to know.

Stylistically, Bull has a painterly economy of means to match the drip-feeding of figurative clues within her works; it is as if she is deliberately using as few brushstrokes as possible to render her figures and loosely depicted backgrounds. Often at crucial moments in her works, in vital passages, she leaves the white primed canvas completely untouched, bare and exposed, as if light itself has bleached out part of the scene. In Smoke (2016) this painterly device is used ingeniously to capture smoke obscuring a youngish man’s face – the puffs and clouds intimated by the absence of paint and the slightest of marks to define their dispersing forms. Bull’s subtle use of colours here – blues fading out to greys, greens dispersing into a tobacco-like spectrum of browns and yellows – brings a sense of optical magic, painterly alchemy to this otherwise unremarkable portrait. On further inspection, it becomes apparent that there is no cigarette or smoking implement in sight, raising small unanswered questions at the backs of our minds as to whether this is tobacco smoke at all, or something more mysterious entirely. The boy’s head, daubed with just a few swift strokes, is as weightless, ephemeral and transient as the smoke in front of his face, raising the tiniest of possibilities that he might not be there at all, just a memory or an apparition. In so doing, Bull has created an unassumingly atmospheric, humdrum yet almost mystical painting that, once seen, is strangely unforgettable.

The bare canvas is used again to great effect in the painting Evergreen (2016), in which a woman – we assume – is seen from behind against a backdrop of trees and bushes. She is wearing a long coat with a fur collar or stole, rendered with so few brush marks that it might feel like a sketch or underpainting. The white canvas, when allied to some electric yellow, green and turquoise outlines, makes the coat appear to radiate bright light, as if caught in the midday sun, or some apocalyptic light. Indeed, one might be forgiven for wondering why she needs to wear a coat on such a sunny day. Her posture – head gently facing downwards, her face blocked out by an uncompromisingly dark shadow, and her right arm pulled in towards her body from the elbow – makes it seem as if she is purposefully trying to avoid something, to protect herself. Her high heels and coat suggest she has been caught out, or found herself in an environment she had not anticipated being in, her formal attire seeming completely incongruous with the sunny vegetation around her. Is she sheltering, hiding, escaping? Whatever the narrative might be, it is fraught with an almost cinematic uncertainty, an underlying anxiety and an overriding feeling of suspense. Bull is happy to pose us more questions than we can find answers to, and this is what gives her works their mysterious edge, an element of the uncanny, and their avant-garde credentials.

But the works described so far do not give a fair representation of the breadth of characters that inhabit Bull’s repertoire, for while there is a sense of shyness and of people trying to avoid our gaze, there are also some much more ostentatious, exotic figures, whether a young woman dressed with wings like a large dark bird (Crow, 2015), a woman sat like a powerful classical goddess in a golden dress and cape with black gloves that nearly reach her shoulders (The Empress, 2015), or two people wearing Indian headdresses (Glade, 2015). In the latter, the pair of figures are wearing brightly patterned kimono-like outfits, though only the most proficient of anthropologists would be able to advise as to whether they are authentic to any particular tribe or culture, or whether they are merely a fancy-dress fantasy. Stood against a luscious green glade, there is, once again, a sense that they are out of context, not in their natural habitat. There is a lot of dressing up, of people wearing costumes and taking on the role of characters other than themselves in Bull’s practice, as if the figures are actors in her paintings, or in their own lives. Here the two faces, seemingly heavily covered in make-up or wearing masks, stare out at us suspiciously or unimpressed – they are somehow both posed for a portrait and caught unawares simultaneously. While fancy dress is usually accompanied by smiles and laughter, the dynamic here is quite the opposite, as if they are not dressing up for public amusement, but rather for something private to them. In which case, we might well ask again what they’re doing here in this clearing in the woods? Is there some strange ritual going on, some roleplay under way, something taboo? It is, of course, also a ridiculous image, an amusing scene underpinned by pathos, creating the curious dramatic and aesthetic tension that is characteristic of Bull’s key works.

Bull’s cast is one of outsiders and loners, mavericks and extroverted introverts, of those with something they wish to hide, or at least to keep to themselves. Sometimes it feels like we should be listening out for a cry for help, of delicate temperaments in need of some moral support. And it is only as one gets further into Bull’s practice that it becomes clear what might be at the heart of the work: a fascination with what is going on behind the mask in people’s lives, what is happening in their minds that might be at odds with, or shape, their physical appearance in the world. How does our outward identity reflect our inner selves? Often awkward, out of context or in a metaphorical no-man’s land, Bull’s subjects are having a spotlight shone on their inner lives, their insecurities probed, or repressed identities discreetly exposed.

Bull’s work explores different states of mind and how these interior lives manifest themselves in, or seek to hide themselves from, the outside world. It is a parade of those outside the mainstream, of sensitive and tortured romantic souls. With an interest in complicated, unusual, dark, idiosyncratic or misunderstood psychologies and personalities, her paintings are investigations into often sidelined or marginalized groups and individuals – people who might be considered on the fringes of orthodox culture and society, or actively excluded from it. Her fascination with outsiders and auteurs, interlopers and lone rangers, strangers and divas, waifs and strays, subalterns and subcultures, finds its expression in painterly paintings with an outsider undercurrent – sometimes haunting and unsettling, often beautiful and ethereal. And, perhaps unsurprisingly, through her exploration of inner and outer lives, she not only challenges conventions of normalcy, but celebrates difference in all its myriad forms.

Matt Price

Image credits from Top to bottom:

Blue Eye, 2016. Oil on canvas, 53 x 45 cm. Photo by Michael Pollard, courtesy of the artist.

Kneeling, 2016. Oil on canvas, 90 x 69 cm. Photo by Michael Pollard, courtesy of the artist.

Statues, 2015. Oil on linen, 98 x 75 cm. Photo by Lucy Ridges, courtesy of the artist.

Smoke, 2016. Oil on canvas, 51 x 40 cm. Photo by Michael Pollard, courtesy of the artist.

Evergreen, 2016. Oil on canvas, 135 x 94 cm. Photo by Michael Pollard, courtesy of the artist.

Glade, 2015. Oil on canvas, 161 x 121 cm. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Stairs, 2016. Oil on canvas, 75 x 53 cm. Photo by Michael Pollard, courtesy of the artist.