Accomplished, beautifully considered shapes and sharp detailing define designer Lottie Robinson’s infinitely covetable menswear collection. Tailoring with a twist takes centre stage and reflects the designer’s love and extensive research into powerful silhouettes of the 80s.

‘For my inspiration in design, I focus upon characters in my life and creative narratives from their interests / upbringing. In the case of my final collection, my grandfather created a dynamic muse. The collection is called The Fine from the name of his sailboat but also fitting to the character himself.’

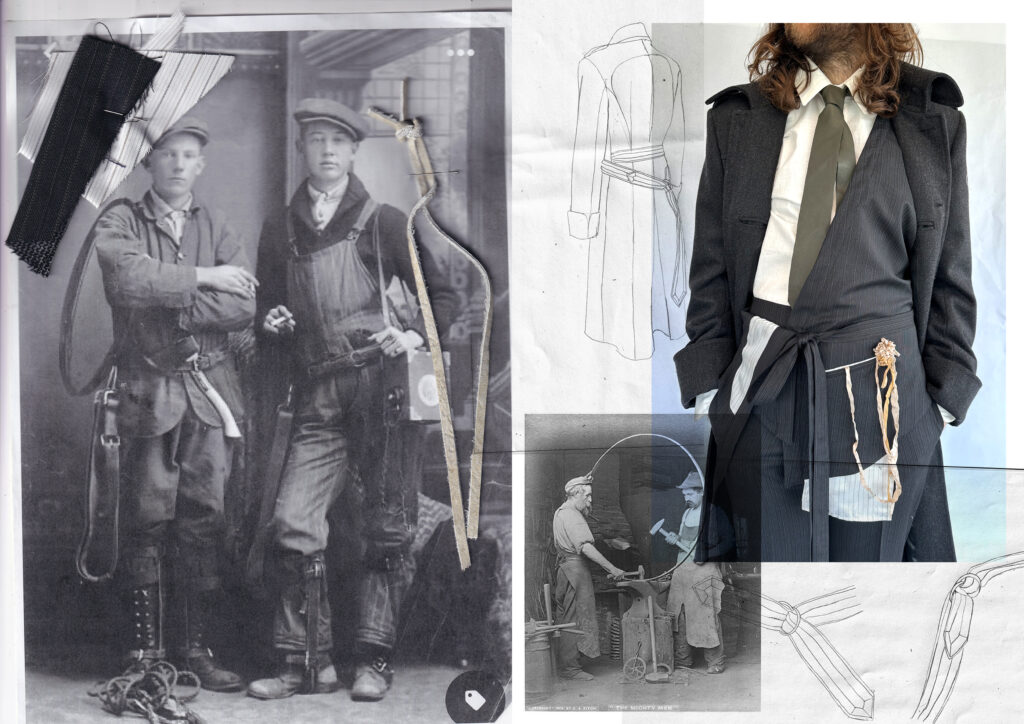

Lottie employs a refined monochrome palette, inspired by vintage photographs. Her skilful, sophisticated pieces are layered throughout with thoughtful, surprising and considered features. Strapping on bags and ties derived from protective aprons soften precise cutting and add delicacy to this consummate sartorial statement.

This clearly-distinctive graduate is one of fifteen thousand fashion-related global graduates to emerge from educational establishments this summer. The statistic is frightening. 15,000. To gain a foothold within the industry, one needs much more than luck. Positioning can take time to arrive at, though some students attempt to pimp a profile via social media, traditional print, even one-off or capsule online sales.

Clothing has always been big business for the UK. The wool trade once accounted for 80% of exports from the British Isles. Now the UK’s Fashion industry is worth upwards of £26 billion & 800,000 jobs to the economy, making it the UK’s largest creative industry. On top of this, fashion’s wider contribution to the economy (known as the indirect, induced and ‘spillover’ effects) in influencing spending in other industries, ranging from IT to tourism, is calculated as more than £16 billion. This means that, including direct, indirect, induced and ‘spill over’ effects, the fashion industry’s total contribution to the UK economy is estimated to stand at over £37 billion.

The Value of the UK Fashion Industry Report, commissioned by the British Fashion Council, defines the industry and analyses the true breadth and economic value of the UK fashion industry for the first time. The industry’s direct economic contribution to UK GDP was collated by analysing the industry’s profits and wages (known as gross value added, GVA) across a wide range of fashion products and items – including womenswear and menswear through to handbags and shoes – plus the contribution of fashion education, fashion marketing and fashion media.

The report also highlights the pivotal role of cutting edge British design and showcasing events such as London Fashion Week and Graduate Fashion Week, in driving innovation and growth within the industry itself, as well as attracting millions of visitors from across the globe to the UK every year.

For so many graduates, the majority are not even close to the starting line as they finish their courses. If nothing’s lined up upon graduation there’s nothing to go to. Nada. Despite the most phenomenal portfolios and dazzling shows, luck does not always go a graduates way, no matter what their hopes. It makes for a cross stitch after years of investment.

Exhaustion levels after the final year means that many veer from graduation show to airport for a holiday in the sun. June slides into July, sways into mad August. Then the reality check of September. Autumn.

Self-promotion is not a dirty term. Self-promotion, away from the area of selfie-absorbed, selfie-deluded, selfie-indulgent social media, which is more about selfie-obsessed selfies to gain a dopamine hit, is a plus. The first week of any creative course should have a focus on CV, press release needs, media needs, industry needs. A creative person needs to create themselves before they ‘do’. I rarely encounter a student who has a press release and accompanying picture set ready to serve during in and around Graduate Fashion Week. Fact.

Luck is the junction of good preparation and opportunity, however, so many don’t have the agency to push forward when (and if) a window of opportunity creaks open. The few who move from last week at uni to the next week as an intern or under contract are few, as competition is fierce. The industry moves at a cut-throat pace. Remember, 15,000 are competing, each and every year, alongside those of a previous year and a previous year and… you get the picture?

Navigating through the portfolios, CVs and occasional press releases during GFW, it was within a visit away from that lucrative herding of hopefuls and hopeless in Bethnal Green to the University of Westminster on Marylebone Road at the height of summer 2023 that I was struck by the sourcing of vintage workwear images unearthed by designer Lottie Grace Robinson and illustrations of real and wearable menswear that reminded me of all manner of creatives who had put their life energy into creating such looks, no longer with us. The 80s, when style bibles such as i-D, Blitz and The Face actually meant so much more than online clicking about. There’s not much value in a like.

Kindly introduced by a member of staff, I met with Lottie who talked of ‘fastened-in’ workwear, which to me had the vibe of early one-offs / limited editions / capsule collections by Christopher Nemeth (RIP), the innovative styling of early i-D contributors such as Judy Blame (RIP), the considered styling & photographic work of Ray Petri (RIP) with a focus on Buffalo, plus Barry Kamen (RIP), his singer / songwriter & model brother Nick Kamen (RIP) and rakish sodomites such as DJ Mark Lawrence (RIP), Alan McDonald (RIP) of Frick ‘n’ Frack @ House of Beauty & Culture (RIP), Andy The Furniture Maker (RIP) in his rough trade drag, Derek Jarman (RIP) in his easy on-off boiler suits. All gone.

The idea of being a survivor of the creative crush back in the 80s and ensuing decades, suffering all manner of wear and tear, is a subject that I entered into at the recent GFW in E2 with Caryn Franklin MBE, fashion and identity commentator / agent of change. What Caryn highlighted is that whilst so many have indeed left this mortal coil, the work lives on and that surviving means that we are still here, still creating, with lots to look forward to.

Lottie Robinson’s collection really gave many a nod in the direction to creators who have left us whose work has, through some form of influence, entered the world in what is often an unconscious or simply unacknowledged, even uncredited way. Once upon a time, if showing beside the likes of Stephen Linard or John Flett (RIP), those in the first wave of i-D and Face discoveries, Lottie would have created a storm. Her collection is worthy of that. File under Future Talent. But is that a possibility now, in 2023?

Louise Janet Wilson OBE (RIP) was a directional British professor of Fashion Design whose spirit is still so very much in the air. An originator, innovator. Louise Wilson was based at the Central Saint Martins College of Arts and Design in London, where she was the course director of their MA in Fashion from 1992 until 2014. She influenced so many key designers. As I was watching Lottie’s models on the runway, I was wondering what Ms Wilson or the likes of shoe designer John Moore (RIP) or even Leigh Bowery (RIP) and his muse, Trojan Name (RIP), Lee McQueen (RIP) might have responded to such final year work. For me, Lottie’s designs showed a continuation, a link with the past, so many pasts and so many passed. Again, real. Wearable. Not infantile panto playtime. I wish I had a magic wand for Lottie in these tough economic times.

Life ain’t always easy and working within the world of Fashion can take its toll. The Fashion industry is a frustration machine, changing every six months with Fashion Weeks all over the planet. This is how you could look. This is how you could feel, should feel. Such dictates. We all needs clothes for a job interview, a work uniform, a wedding, baptism, funeral. Clothes to run in, dance in, flirt in, fuck in, riot in.

Whilst Lottie has been fortunate with work placements within Craig Green, where the main part of her role was sewing fully lined / trimmed toiles, fabric manipulation, samples and fabric sourcing. Lottie has also served internships alongside designers such as Olubiyi Thomas and Saul Nash, hopes for this bright spark’s next stage are high.

Lottie tends to invent a character and proceed from there.

‘For me, menswear is storytelling and dressing the invented character. The loud research and references made subtle,’ Lottie says, of her process. ‘I’m interested to see over the years how my muse will change. Will the man I design for change much?’

Of materials, Lottie states, ‘Organic fabrication, wools, cottons and leather excite me most.’

So many students who leave a course with no future placement in the diary invariably face the task of application after application. As a mentor, I encourage students to really imagine, have a vision, dream a dream and to go with. Whilst some many wish to work in Tokyo with a designer such as Takeo Kikuchi in Shibuya or the team at Christopher Nemeth in Omotesando, some settle on what’s on their doorstep in the UK, compromising aesthetics.

Fact is, in terms of The New Breed within so many of the UK-based graduates, which includes oversees graduates, so many are slipping through the net. When a window of opportunity does arise for The Next Wave, some just don’t have that internal mechanism on standby, ready to press the SEND button. If Future Talent don’t move fast, how quickly that window of opportunity slams shut.

Here’s wishing graduates from the University of Westminster good fortune. Azita Thanigasalam, Grace Tayo, Constantine Corney, Eliza Douglas and Nully Amiri, all alongside Lottie Grace Robinson, I wish you all the very best. With fifteen thousand others possibly chasing the same dream ever since the first GFW back in 1991, you have to compete in the most ruthless style.

With love,

Peter Paul Hartnett

Curation by Peter Paul Hartnett

The Hartnett Archive @ Camera Press