In autumn 2014, London-based British artist Cara Nahaul returned to London with an MFA following a prestigious year-long Fulbright Scholarship at Parsons in New York.

The Goldsmiths graduate already had a number of accolades to her name, including a Jerwood Painting Fellowship and being shortlisted for the John Moores Painting Prize, and no sooner had she set foot back home then she was awarded a residency with the Florence Trust in Islington. She participated in ten group shows in the UK and USA during this time, which is both a logistical marvel and a testament to the energy and drive that must inevitably lie beneath her calm, serene, easy-going exterior. And perhaps the cherry on her 2015 cake was being invited to have her first ever solo exhibition. Dynamic gallerist Christine Park, who established a London space in Fitzrovia in autumn 2014, spotted Nahaul’s work at the Florence Trust summer exhibition 2015 and soon after called to offer her a solo show.

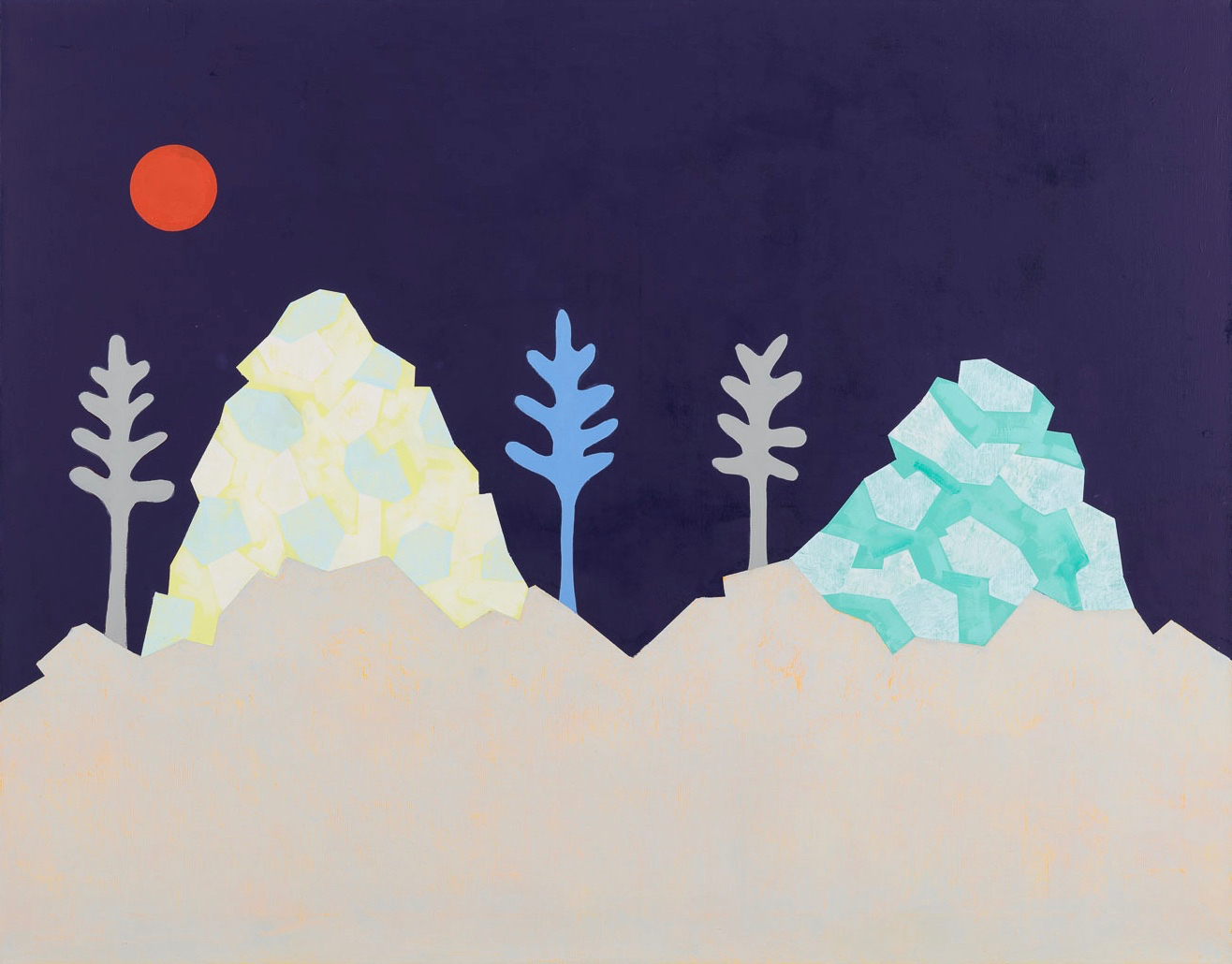

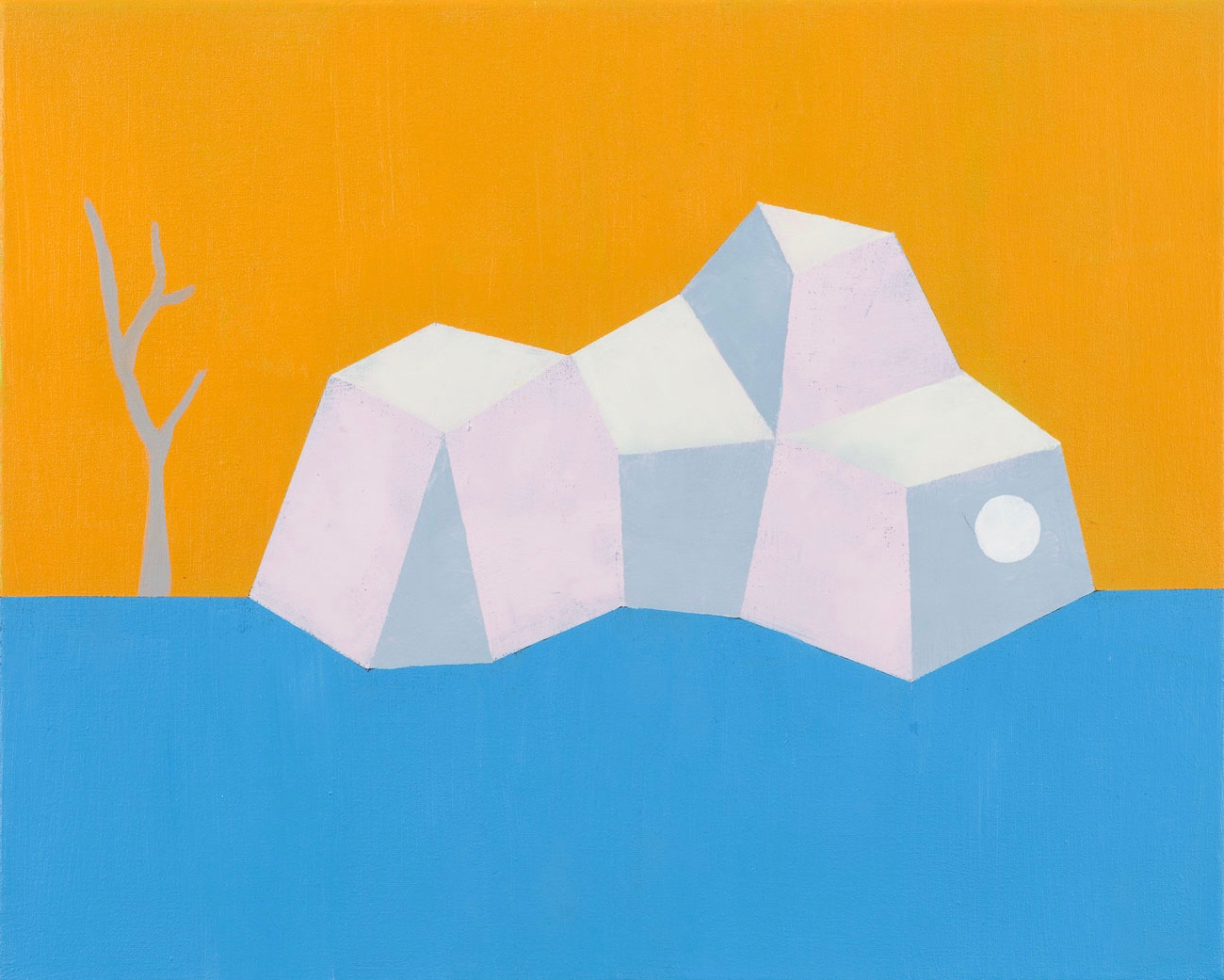

The resulting exhibition, Crossing the Tropic, opened just a couple of months later. The exhibition presented a body of work that revolved around the idea of tropical islands, in part inspired by Nahaul’s mixed ancestry from Mauritius and Malaysia, on either side of the equator and separated by several thousand miles of the Indian Ocean. Metaphorically crossing the Tropic of Cancer on our journey south, Nahaul takes us on a seemingly gentle adventure into an exotic imaginary, to a land of crystalline geology and otherworldly colours, from blood-red soil to pastel-green skies and candyfloss rocks. But while the landscapes she creates are exotic (if not mildly hallucinatory), beyond the occasional palm tree they are not the kind of tropical landscapes one might expect of islands around the equator. They are more lunar than luscious, more Martian than Mauritian. Of course, it should be noted that some islands in the Indian Ocean are more like the moon than an earthly paradise, depending on the magnitude and recentness of volcanic activity, among other factors. In one work a single flower sticks out from grey rocky ground; in another branches are exposed as if autumnal trees, with just a sparse sprinkling of multi-coloured leaves. And this is where we realise that Nahaul is as quick to unravel our ideas of the exotic as she is to take us towards them. There is a sense that we are being encouraged to un-imagine the exotic, to un-think the tropical imaginary. For Nahaul’s landscapes are undeniably charming, curious and pleasing to the eye, but they are neither the stuff of fictional paradise nor the luxury holiday destinations we see in magazines and online from underneath our grey, British clouds. No, they are something else entirely.

These quirky landscapes teeter on the brink of abstraction, with stark horizons and three-dimensional forms threatening to become flat, almost falling in line with the surface of the canvas. It is as if she wants to strip out perspective and reduce physical space to its most basic elements. And then, of course, it hits you: she’s brought us to a fundamental crossroad of painterly languages – the fork in the road where painting either turns to face figuration or abstraction. In stripping out, paring down, and flattening her chosen motifs from the natural world, Nahaul’s landscapes edge towards leaving depiction and representation behind, their organic forms the only things stopping the paintings slipping into pure abstraction. Nahaul then proceeds to pose us another conundrum – are we to read these paintings within a discourse of abstraction, modernism and minimalism, or within a discourse of non-linear perspective? Add into the equation ideas of Western and non-Western traditions of image making, ask who is doing the looking and where from, and we start to get closer to Nahaul’s own thinking about her work. At what point do geometric shapes start to take on cultural, geographical and historical meaning? When does abstraction cease or start to be Western, and what does that even mean today? How is it that some visual languages can retain a sense of universality, while others can have such localised or specific connotations? How, when and why do visual languages move around, evolve, change and adapt? Who owns and who co-opts shapes and patterns, and for what purposes? Can anything be indigenous today, and what do homogeneity and globalism mean now for the younger generations?

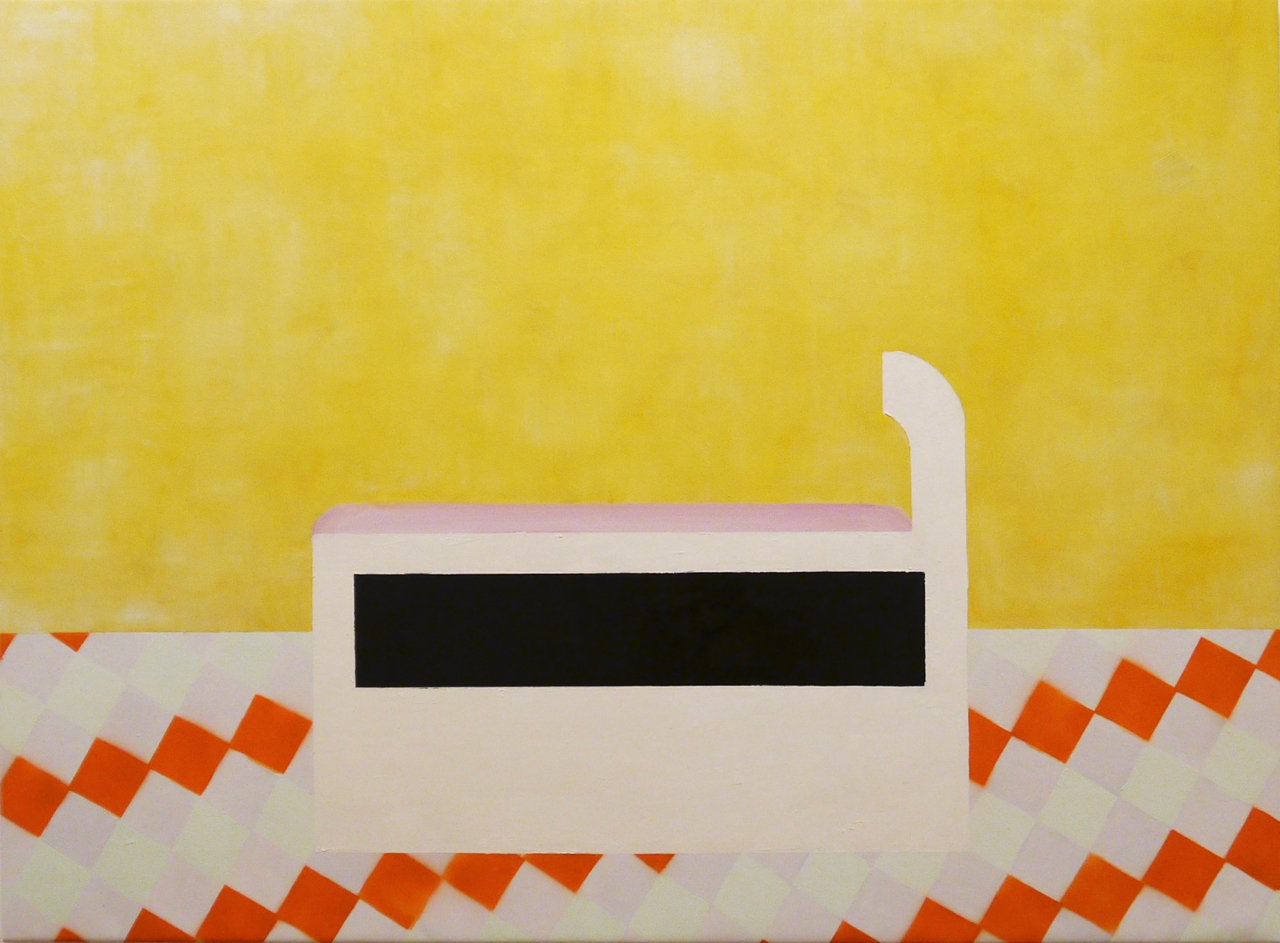

Nahaul’s interest in the intersections of Western and non-Western forms of representation and abstraction can be seen more literally in the body of work created prior to the Islands series. In a two-person exhibition with Matthew Krishanu entitled Another Country at the Nunnery Gallery in Bow, London, in 2014, Nahaul presented large canvases that explored this interface from various angles. In one, a bed-like form rests on a diamond-patterned floor against a yellowish wall – it has a vaguely Middle-Eastern feel, though could equally be North African. In another, an empty chair (as if inviting us, or herself, into the image) sits between a leaning palm tree on one side and a free-standing lilac wall on the other: the man-made and the natural, the tropical and modernist united against a backdrop of thick yellow and white stripes. Across this body of work one had the sense that she was pushing different buttons to see what they might do – smearing and smudging, scuffing and erasing, juxtaposing and superimposing – as if seeking out a new semi-abstract language of her own, and in the process trying to pin down precisely what her critical position might be in relation to it.

The Island series is certainly much cleaner, tidier and more resolved than the works from the Nunnery show, though there is a sense that we might simply be passing through the next stage of our journey with the artist. She made it to her islands, has explored them, and is ready to move on. And it looks like we might not have to wait long until we arrive at the next destination on her/our travels, as a visit to her studio in central London one beautiful spring afternoon made clear to me. Up on the walls were the first of a new series of works in which interior spaces are fused with the outside, where architecture meets garden. Intrigued by the history of gardens created out of context – a Japanese garden in South London, for example, an English country garden in South Africa, or a European colonial garden in Australia – Nahaul has been thinking about dislocation, relocation, and re-siting, about things being taken from one place to another, and on what terms. Indeed, horticultural metaphors such as ‘uprooting’, ‘transplanting’ and ‘landscaping’ are perhaps increasingly useful for thinking about her practice.

Sometimes things that are taken into a new context look odd or awkward, sometimes they look special and exotic, sometimes they just kind of blend in, as if they have always been there. Nahaul seems to be working through these ideas on both a micro and macro level – from a lone plant in a pot through to the geo-political paradigms that are shaping the discourse of the Other, of the post-Colonial condition, and of diaspora today. In her sketchbooks, it was a revealing and perhaps surprising insight to glimpse study after study of statues, statuettes and figurines from diverse ancient civilisations from around the world, suggesting she might even be quietly contemplating revisiting the twentieth century’s complex of Western aesthetics, global Modernism and notions of Primitivism. (Not to mention circumnavigating ideas around the global market for art and antiquities, museum acquisition and display policies, and contentious issues of repatriation of works to their homelands.) Simultaneously, with more than a nod to colour-field, hard-edge and neo-geo painting, Nahaul’s still-germinating series of new works promises a refreshing perspective on geometric abstraction in the West and the (largely patriarchal) cultural politics that it has come to represent. There are many ways to change a debate. While Nahaul is naturally humble and understated, the scale of ambition of her journey is clear: she’s searching for new lands, not simply island hopping…

Words: Matt Price

Images from top:

Cara Nahaul, Islands, 2015. Oil on canvas, 110 x 140 cm. Photo Mark Blower. Courtesy of Christine Park Gallery.

Cara Nahaul, Grey Sands, 2015. Oil on canvas. 100 x 110 cm.

Cara Nahaul, High Tides, 2015. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 100 x 120 cm. Photo Mark Blower. Courtesy of Christine Park Gallery.

Cara Nahaul. I Hope the Moon is Listening, 2015. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 110 x 140 cm. Photo Mark Blower. Courtesy of Christine Park Gallery.

Cara Nahaul, Obsidian Sky, 2015. Oil and acrylic on canvas 40 x 50 cm. Photo Mark Blower. Courtesy of Christine Park Gallery.

Cara Nahaul, Nelumba Lucifera, 2015. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 90 x 100 cm. Photo Mark Blower. Courtesy of Christine Park Gallery.

Cara Nahaul, Oasis in the Park, 2015. Oil, acrylic and flashe on canvas, 110 x 140 cm. Photo Mark Blower. Courtesy of Christine Park Gallery.

Cara Nahaul, Untitled. 2013. Oil, enamel and spray paint on canvas. 120 x 160 cm . Photo: Studio Cara Nahaul. Courtesy of Christine Park Gallery.

Cara Nahaul, Sit and Pry, 2013. Oil and flashe on canvas. 120 x 160 cm. Photo: Studio Cara Nahaul. Courtesy of Christine Park Gallery.

Cara Nahaul, Sanctuary in Blue, 2016. Oil and flashe on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Photo: Studio Cara Nahaul. Courtesy of Christine Park Gallery.

Cara Nahaul, Pink Plane, 2016. Oil and flashe on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Photo: Studio Cara Nahaul. Courtesy of Christine Park Gallery.

Cara Nahaul, Octopus, 2016. Oil on canvas. 50 x 60 cm. Photo: Studio Cara Nahaul. Courtesy of Christine Park Gallery.