CAROLINE WALKER: CALIFORNIA DREAMING?

It’s easy to be seduced by Caroline Walker’s paintings. They often take us into stunning private houses and estates – the kinds of places we might only ever see in films or on TV. There are beautiful modernist buildings, amazing manicured gardens, immaculate sun-drenched bathing terraces, and sky-blue sparkling swimming pools.

While many of these locations are for the wealthy elite, the doors are often opened for Walker by her ever-growing reputation as one of Scotland’s leading painters of her generation. But Walker isn’t just showing us places we might aspire to visit, live in, or even to own – far from it, in fact, for there is always something more complicated and mysterious underlying the outward appearance of beauty and luxury in Walker’s world, and it kind of depends who we think we’re looking at, and, of course, who’s doing the looking…

The intrigue begins when it is established that some of the people in Walker’s paintings are unwitting protagonists, snapped unawares or without forewarning, while others are models and actresses who have been carefully chosen and primed for their roles. This might involve specially selected outfits and accessories, make-up and styled hair (Walker is no stranger to wigs in her backstage wardrobe) or choreographed instructions about where to stand, what expression to hold. Her cast – which to date has been almost exclusively women – spans many ethnicities, ages, backgrounds and types.

Walker has, ever since studying at Glasgow School of Art and the Royal College of Art, quite consciously sought to explore representations of women in her work, and to do so in ways that not only challenge conventions in art history, but also perceptions and attitudes that are deeply ingrained in our (still!) patriarchal society and manifested throughout visual culture today.

The relationship between women’s inner lives and outward appearances, and the relationship between the physical places in which they spend time and the underlying structures that control these places and hence women’s lives within them, are central to Walker’s practice.

In 2015, Walker went on a research trip to Los Angeles and Palm Springs – a beacon for those dreaming of sunshine, pools, glamour, fast cars and money.

In the work Sunshine Court (2016) we see some kind of luxury garden or resort saturated by bright sunlight, the shadows of tropical bushes and trees falling onto a wind-break or privacy fence, immaculately kept grass and the edge of the inviting pool behind. A young lady sits on a bench next to a pile of neatly rolled towels. She wears an all-white outfit – a knee-length dress or skirt and top and white trainers, her hair in a ponytail that hangs forward over her shoulder. We don’t know if she is a guest, member of staff or even the owner, though our instinct, for right or wrong, might lead us to assume that she is a towel girl – a member of the leisure staff whose job it is to hand out clean towels and collect ones that have been finished with. If this is her job, then it looks like she is either waiting for the first guests of the day, is off-duty or simply caught unawares as she sits informally, alone with her thoughts. Behind her is a large, rectangular tent-like structure, with white curtains tied back by black sashes and large fans hanging from the ceiling. An outdoor dining area or simply a cool place in which to seek shade from the Californian sun, the space is clearly designed for some serious relaxation, and we are left pondering who this young lady might be, and whether we were wrong to assume anything about her and her status from her appearances.

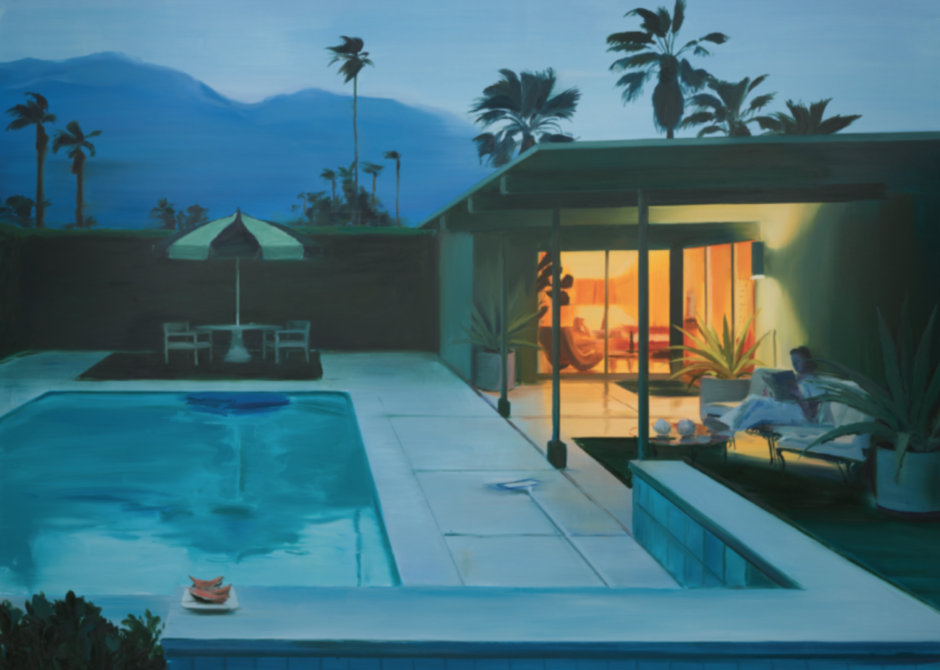

In Desert Modern (2016), Walker takes us to a mid-century modern building in Palm Springs – one of three venues she stayed in during her trip. The work captures another poolside location, this time at dusk, with a cool blue light falling over the scene. In the distance, purplish hills fade into a light blue sky, with palm trees silhouetted against them. A neatly trimmed hedge offers the pool privacy, and a small seating area replete with stripy parasol suggests this might be a private villa rather than a conventional hotel complex. On the right, a woman sits reading a magazine in shadow under an architectural canape extending out from the villa. Through some glass doors we see into the living room of the villa behind her, with electric mood lighting casting its light onto the patio outside.

A figure sits inside, casually resting their head on a bent arm. The scene is one of relaxation, peace and quiet, and yet there is something dramatic underlying it, a tension of some kind, partly evoked by the fact that we the viewer are looking on from behind a low wall, as if a voyeur or unwelcome guest. This undoubtedly contributes to the cinematic sense that Walker has created in the painting, like a scene from some Hollywood movie. Writing about Walker’s LA trip in the catalogue for a group exhibition at Lin & Lin gallery in Taipei this spring, curator Helen Carey asserts ‘Maybe nothing is quite real, maybe it is a fiction based on an imaginative idea of what reality in a luxurious paradise should be; maybe it only just masks a different, darker reality or truth’.

Walker’s LA and Palm Springs series leads us through a variety of indoor/outdoor spaces, staring at bikini-clad bathers who perhaps don’t know we’re there; into the dressing rooms of women preparing for an evening out; catching a young lady entering a villa who might have sensed us in her peripheral vision; and lurking in the darkness looking through people’s windows and doors. Maybe it’s all innocent enough, but there is an underlying sense of something more sinister at play, and as viewers we’re implicated in that. In the process, Walker is clearly subverting or undermining the male gaze, surreptitiously taking control from the patriarchy which, with her wonderful lightness of touch, she so regularly runs rings around in her painting.

Matt Price